Photo: Sundance Institute

An empty parking lot is an empty parking lot. What happens, though, if an off-screen voice tells you there could be a serial killer lurking somewhere around that parking lot? And what happens if that off-screen voice then tells you that there would be a serial killer lurking there, if only the off-screen voice had been able to make his true-crime documentary about the serial killer, so instead now the parking lot remains an empty parking lot, albeit with all this once-latent, since-dissipated potential? Charlie Shackleton’s sly film Zodiac Killer Project lives inside this conceptual limbo — nebulously sinister and dryly hilarious all at once. A work of criticism as well as a work of art, it’s a sharp takedown of our culture’s obsession with true crime, identifying and skewering the genre’s most familiar tropes even as it playfully indulges in them. Premiering at the Sundance Film Festival ahead of what one assumes will not be a major streaming debut, it also questions the reasons for our fascination with such stories. True to form, it demonstrates some of those very reasons. Honestly, Netflix should buy it, then pump it out and watch the “views” roll in. We’ll all be too busy folding laundry and ordering delivery and texting to notice that what’s onscreen is not the real thing but a poisoned palimpsest.

As Shackleton tells it, not long ago he was on the verge of producing a true-crime series about Lyndon Lafferty, a California Highway Patrol officer who once came face to face with a man he became convinced was the notorious Zodiac, the Bay Area serial killer who operated for years and evaded identification and capture. After his superiors nixed an official investigation, Lafferty spent the ensuing years trying to build evidence against the man, whom he called George Russell Tucker (a pseudonym, evidently). He published a 2012 book about his freelance efforts, titled The Zodiac Killer Cover-up: The Silenced Badge, which Shackleton had intended to turn into a mini-series. Although he never really saw himself as that kind of filmmaker, “working in documentary these days, true crime has this gravitational pull,” the director observes in voiceover. “So you eventually kind of give in to it.”

Then, in the midst of contract negotiations and preproduction, Lafferty’s family decided they didn’t want to move forward, and the bottom fell out of Shackleton’s project. So, instead of his intended reenactments and interviews and creepy montages, the director now narrates his tale over deserted streets, anonymous storefronts, empty living rooms, random churches that might have once been locations for his pseudo-narrative. “Fuck, it would have been good,” he sighs, as he launches into a fake credits sequence made up of the credit sequences of other, existing true-crime series, all the while pointing out all the elements such sequences require: the layered imagery and the shadowy figures, presented with a “disheveled, scratchy aesthetic, as though it’s been made by the serial killer themselves.”

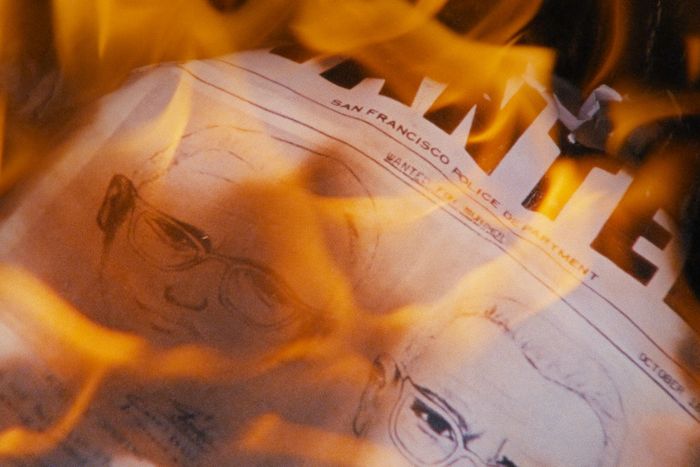

In deconstructing a genre, Shackleton by extension deconstructs his own film. As he laments his aborted project, he gives us enough of what the finished show would have contained. He also tells us what he’s giving us: the cutaways to police sketches and tables full of files; traveling shots of highways and hills; slow, menacing zooms into empty streets; and of course the close-ups of hands and feet and eyes and tape recorders, all that so-called “evocative B-roll” that marks so much true crime.

At times, it feels like he’s taking the austere, observational, experimental approach of landscape filmmakers like James Benning and Jenni Olson and giving it a self-aware, narrative spin. The laid-back voiceover and long shots of abandoned spaces settle into the easy rhythms of a genre that flattens the spectacle of human cruelty into zero-effort comfort viewing. The film has its set-up, its narrative development, its climaxes and red herrings and high moments of suspense. We might even wonder if all those empty spaces are, in their own way, even scarier now, still full of ominous potential in the wake of Shackleton’s supposedly failed narrative. We do walk away from this movie having learned something about Lyndon Lafferty’s story and might feel a couple of affirming chills up our spines.

That’s sort of the point. Zodiac Killer Project’s real target isn’t true-crime docs, but something grander, more societal. The film explores how form conjures the illusion of consensus. Shackleton’s transparency in presenting such elements, while informing us that he’s presenting them in precisely the way the true crime genre has taught us to expect them, breaks a cognitive fourth wall. We’re charmed by the evidence of our own manipulation, but we also become aware of how these clichés we’ve come to know and love create meaning — how guilt can be spun out of thin air, and how the demands of narrative will always supersede the messy nature of truth, be the venue a theater screen, the so-called boob tube, or life itself.