On David Lynch’s passing, and memories of the diner scene: “The dread just came to me. I can feel it in my chest right now.”

Photo-Illustration: Vulture; Photo: Universal Pictures

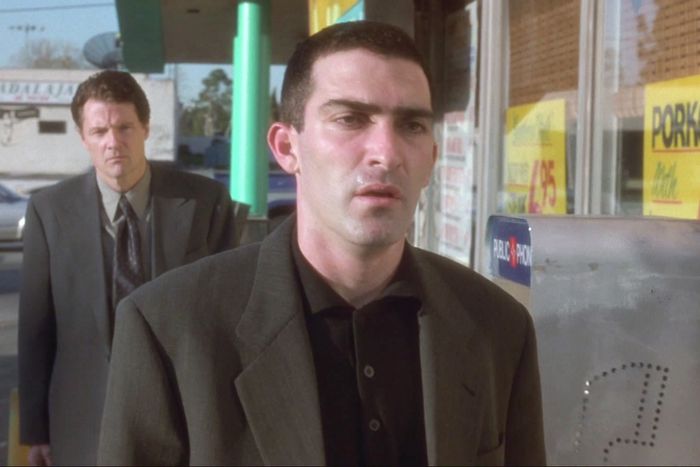

If David Lynch’s work can be boiled down to a handful of scenes, as many people have done since he died this month at age 78, the Winkie’s diner scene from Mulholland Drive looms especially large in the pantheon. It arrives 12 minutes in, establishes no immediate connection to the rest of the plot, and feels far more traditional than, say, a woman inside a radiator singing about heaven. Lynch, master of the uncanny, provides the biggest jump scare of his career via a simple besuited guy named Dan (Patrick Fischler) who recounts to a dude named Herb (Michael Cooke) his vivid dreams about a spooky man out back. “I hope that I never see that face, ever, outside of a dream,” he says. The sequence’s familiar horror-movie grammar — surely nothing is lurking behind the building, right? — is hypnotizing. Lo and behold, Dan does see that face, and suddenly Mulholland Drive has threatened to make the eeriest nightmares come true.

Fischler was a young character actor in the making when he shot Mulholland as a TV pilot that ABC infamously passed on. A few years later, after Lynch had released the longer version that is arguably his defining film, Fischer became one of those actors who pops up to steal scenes with his distinct, piercing gaze. He credits much of that fortune to Lynch, whom he’d long admired.

“I grew up in front of the TV; I was a latchkey kid,” Fischler tells Vulture. “I watched TV all through the ‘70s as a little kid, and then the ‘80s were my jam. Then, when Twin Peaks came on, I didn’t realize television could be that different and weird. I don’t think anybody did.” Fischler went on to appear in several shows that owe a debt to the watercooler analysis Twin Peaks inspired, like Lost, Mad Men, Southland, American Crime Story, and Barry. His experience on Mulholland Drive, and his affinity for Lynch, came full circle in 2017 when he appeared in Twin Peaks: The Return.

In the wake of Lynch’s death, Fischler reminisced about shooting the Winkie’s scene, what it might mean, the crucial notes the director gave him, and the time Lynch meditated his way to a brand-new Twin Peaks scene midshoot.

Tell me about your first interaction with David Lynch.

I went in and met with Johanna Ray, who was his casting director. He didn’t audition actors. You didn’t get sides, you didn’t get a script, you didn’t get anything. She would talk to you: Where are you from? Tell me about your parents. I would talk about my upbringing, and I have lots of different traumatic stories as a child that I talked about. Then I got a call saying, “Hey, you just got cast in this ABC pilot, Mulholland Drive.” I was like, “What, what? You don’t want me to audition?” Johanna said, “No, no, David just watches videos of people talking about themselves,” which is remarkable.

Had David sought you out?

I got submitted by my agent at the time, who just said that David Lynch was casting an ABC pilot and looking for different types. She would show David these interviews, and then he would pick his cast. So I got the offer to do it and the pages of the scene — that’s all I got. It was like making a short film. I had a little bit of a freak-out. I was 27 and thinking, I have to do this monologue for David Lynch. I mean, I was 13 when Blue Velvet came out, and it changed the way I thought of movies. So I went to set, and god, this is all so weird: I’d brought my own bad ‘90s Hugo Boss suit because they called and asked if I had a suit I could wear. I met David for the first time on set at the diner we shot at. They always say don’t meet your idols. Meet your idols if they’re David Lynch. Truly. He was warm and kind and open.

Did you have any other information about the rest of the pilot?

I knew it was a pilot about a girl in Hollywood. I later saw the script, after we shot, because at that point I was part of it and I was curious. I should have kept it, but I didn’t. So when I shot it, I did not really know anything about it except my scene. I went in kind of blind.

Is the scene you shot for the pilot the exact same Winkie’s scene in the film?

Exact same. The pilot was 90 minutes plus commercials, so I would say the first hour and a half of Mulholland Drive is very much the pilot. The rest are the reshoots and the stuff that he did when ABC passed, which of course they did. Can you even imagine Mulholland Drive the TV show?

It’s even more unimaginable than Twin Peaks the TV show.

One hundred percent! Because Twin Peaks is at least kind of linear.

And it’s really a soap-opera mystery in a way.

Exactly. Now, if this was just going to be a tale of Hollywood, I think it would have been a remarkable TV show. But I think it would have made people a little crazy. I always hate to say too much because I like people to have their own theories, and I’m not sure if this is my interpretation or something I just felt about David, but people come up to me all the time and ask, “What did your scene mean?” And I say “What do you think it means?” Then they tell me whatever theory they have — there’s about, you know, 30,000 — and I just say, “That’s it.” So I try not to give too many actual facts, but my memory is that we’re agents. Most people don’t get that right.

Oh. Okay, yeah, I guess I didn’t realize that.

People are like, You’re talking to your shrink, and I’m always like, You don’t meet your shrink in a diner. Or they think we’re producers. If my memory is correct, we were agents, which makes sense.

Photo: Universal Pictures

Did David tell you that?

That is my memory of what David said to me when I asked, “Why are we in this world? How are we part of Hollywood?” The movie has actors and directors and producers, and you need an agent in Hollywood. So I don’t know where it would have gone, but I would have been in more episodes and there would have been more of that story. But it’s so much better that it’s that one scene and that’s it.

When ABC passed, I assume you just thought, That’s a project that won’t see the light of day. It happens, especially in TV. But it didn’t take terribly long for it to be put in turnaround and become a film. Were you looped into that process?

I got a letter from David saying that StudioCanal has offered a small amount of money for me to do some reshoots and add some stuff to turn this into a feature film. We had to work for scale, but of course I said yes. There’s that shot in the last 20 minutes where she’s at the diner and sees me. That was shot for the movie.

That’s the only thing you did during pickups?

Yep, and I have very little memory of shooting that, really, which is funny because my memories about shooting the pilot are so deep and profound because David really changed who I am as an actor. If I were to credit anybody for my ability to capture some stuff on-screen, it’s all him.

When we shot that original scene, I had done some stuff, but never anything substantial. I’d done a lot of theater, and I was, for lack of a better word, big on-screen. I had not found film acting, which is so different. We rehearsed the scene, and I kind of sucked. I did too much. But David being David, and being so incredible, he just slid up in the booth next to me and said, “That was great, that was great. But, you know, he just had a bad dream. That’s all.” I looked at him, and I could tell what he was saying to me. He was like, “That’s enough, right? You’re telling your friend it was a bad night.” What I was doing was adding on and not just making it simple. Then that was it — he never gave me another direction again. I was able to realize, Oh, I’m enough. Being simple is enough.

I can picture him saying all of that in my head. There’s an actionable item within the note — but there is also a specific cadence to that monologue. Maybe it has to do with the way the camera cuts between the two of you, but the way you deliver the lines slowly and take pauses feels very precise to me. He didn’t guide you through any specifics there?

No. Really, I was scared to say these words out loud, so there were pauses, not intentionally. A lot of the dread and the fear there are his shots, his music, his editing. That’s all it is. So no, he did not get specific about cadence or pauses. That’s not who he was at all.

All Lynch disciples know that he loves to wink at the audience with his casting choices, like hiring Hollywood legends who haven’t worked in a long time, like Ann Miller in this film. Or casting various outsiders, or someone whose presence is kind of an in-joke within the industry. I actually learned just a few days ago that your father owned a Hollywood establishment named after you that’s very similar to Winkie’s. You could read your casting as a wink about Winkie’s, if you will. Was that ever discussed?

Not at all. Yes, the Roadhouse was huge in the ‘80s. I love that theory. I believe David would have talked to me about it, but it never did come up. I think it’s one of those unintentional weird moments. Or David just kept it to himself. I don’t know if I talked about the Roadhouse in my casting interview. I had only done a couple of TV guest spots and tiny roles in Speed and Twister, so I don’t think he made the connection. But you know what? Maybe.

What was the diner where you guys shot?

It was a real diner. People think it’s in Hollywood, but we were out, weirdly, in the Torrance area. If my memory serves, it had closed down but was still the same inside. They rented it.

And the whole thing was shot there, including the walk outside to the back?

All of it.

Before you did the first take of the walk, had you seen what the person behind the dumpster looked like?

No. I don’t think I saw it until we did the first take. That was Bonnie.

What was that first take like for you? It’s a jump scare for the audience.

It was kind of a jump scare for me. It was like, Oh, shit. In person, she looked remarkable. It was scary and odd and creepy. In that whole scene, even the walk, the dread just came to me. I can feel it in my chest right now talking to you. I’m not that kind of actor.

You don’t usually take it home with you.

I don’t even take it past cut. Right now, talking to you about it, I’m sweating a little bit and I can feel it. That was an incredible thing to find on that walk. He told me specific things to look at, like the phone booth — that was choreographed because it was Steadicam.

How many takes did you do?

We did not do very many takes of that, like two or three. We did more takes inside the diner. David wasn’t a guy who did 50 takes anyway, or not on my stuff with him.

You mention Bonnie, who plays the “man behind Winkie’s,” as this person is called. It’s interesting because the quote-unquote man is played by a woman, and when he emerges, I think he has fairly feminine features. But even the clues Lynch later wrote about the film say, “Note the occurrences surrounding the man behind Winkie’s.” He uses a masculine noun, but there’s an inherent androgyny. Did you guys discuss that?

That was not ever talked about, and I didn’t see that sort of androgyny. In my mind, it really seemed like it was a man. And I know what you’re talking about because I see the face right now and it could be anything, but I didn’t see it as that. My character says, “There’s a man,” so it was just always a man to me. But who knows why David cast Bonnie. It’s a great choice.

Mulholland Drive comes out in 2001 and takes on a life of its own. This scene in particular is often ranked on lists of the scariest horror moments of all time. What was it like to see the movie get released?

My wife and I went to whatever the L.A. premiere was — something at the DGA. I hadn’t seen the movie yet, and I was completely blown away by it. But something has happened in the last 20-odd years where the scene has become more and more of the scene from the movie. It was not that when it first was released. Silencio was talked about more. But David was nominated for an Oscar, and who knew it was going to be this incredible thing? In terms of me and that scene, I didn’t really feel anything different. But it started to change. I’m in my 50s, and there are a lot of filmmakers now who would watch this movie when they were young or in college. Over the last 10 years, with any director I meet on almost any job, Mulholland Drive comes up. I don’t find it as scary as people find it, but I wonder if Mia Farrow thinks Rosemary’s Baby is scary.

We talked about the slowness of the monologue, but the slowness of the walk feels almost interminable, in a really thrilling way. Did it feel like a long walk to you?

Yes. David did tell me he wanted me to go slow. What’s remarkable about David — I’m going to miss him so much, and the world of television and movies is going to miss him — is that on 99 percent of jobs I do, the note is “pick up the pace, pick up the pace, pick up the pace.” It’s exhausting because human beings don’t speak that way or walk that way, but you get it in a lot of notes. But David never told me to go faster. He loved how slow I went. He wanted the audience to be uneasy. If I’d spoken that monologue fast or walked fast, it doesn’t give you time to be fearful of what’s about to happen.

Some people think of this scene as the movie’s thesis. It’s about the contrast — or lack of contrast, perhaps — between dreams and reality, and the fact that your worst nightmare could actually be lurking around the corner.

Yes. My friend who had never seen the movie before was like, “Your character is an actor, right? He came out here with the dream of success, and now the monster is failure.” That’s great. Sure. I love it. I think there’s a reason the scene stayed in the movie.

Had you and David stayed in touch between Mulholland Drive and Twin Peaks: The Return?

No, so when I heard about Twin Peaks, I was like, “Oh my god, please let there be something for me.” Then I got the call. I would have dropped anything. I would have quit another job to do it. I was lucky it shot on a Saturday. Then I got sent the scenes, and we were going to do it all in one day even though it was five episodes. I was like, “This is awesome. I don’t know what any of it means.”

You had no further context about the show? Did you ask questions?

No. I didn’t want to know. I’m so glad I didn’t, but in my mind, like everybody, I thought, Oh, this is going to be about those characters and the original show. I think Showtime must have been a little like, “Wait, what?”

I think they were, yes.

And yet I thought it was brilliant. So, no, I did not ask any questions. I didn’t work with anybody besides the guy who played my assistant, Jennifer Jason Leigh, and Tom Sizemore. I think even Jennifer only knew her scenes. It wasn’t like the bigger stars got the full script. I’m sure Kyle MacLachlan did, but we all just knew what we were doing.

You talked about that great note David gave you at the diner. Did you get anything memorable on Twin Peaks?

I’ve never told this story. We had all the scenes, and after we finished one scene, David went into a sort of meditative state. Everybody got quiet, and we kind of sat around.

Do you mean a literal meditative state?

I do. He sat there in his chair and he meditated.

How long did this go on?

I think a couple of minutes. It wasn’t transcendental — it wasn’t that deep, but I think it was meditative. And he came out of it and wrote a scene, handwritten on paper, and gave it to the actors and the script supervisor. I think it’s my first scene: “Why do you let her do this stuff to you?” He wrote that scene in that moment, and by the way, it’s my favorite scene in all the episodes I’m in. They were not these huge scenes, but that one had an element of dread. In my mind, it pieced everything together. Without it, it’s not that interesting an arc — you just look at this guy in his Vegas office for whatever reason. It’s kind of remarkable, and that was my lesson that day: Goddamn, the word “brilliant” is just the full definition of David Lynch.

Did your paths cross again post-Twin Peaks?

They never crossed again, and without dwelling, I feel sad. I wish I’d seen him or talked to him one more time, just because I’m not quite sure I ever told him how much he meant to me. I’m not a big regret guy, but that’s a bummer to me. On Twin Peaks, I did hug him and tell him how great it was to see him again, but I never got to take two minutes to tell him that he was a huge factor in my life. You can name a million directors who are so brilliant, but David represented more to people. He changed television and movies forever. Twin Peaks: The Return came out when people thought everything had been done on TV. He was like, “All right, you want to see something different?” My daughter is 15, and she wrote me from school, “Papa, David Lynch died.” She was freaked out for me. She was like, “We have to decide what we’re watching first.” I’ve never shown her his movies. I get scared to show her stuff, because I’m always like, “Wait, what if she doesn’t like it?”

What about Eraserhead? You can just start at the beginning.

I think it would blow her mind. Maybe Blue Velvet. He’s got incredible work that will live on forever, and I’m so fortunate that I have a scene in a movie that will be around forever.

Bonnie Aarons also plays the eponymous nun in The Nun. In 2013, she explained the Mulholland Drive shoot to Vulture like this:”They said I was going to be a character called the bum, and it was going to be a bunch of special effects. But that is all real makeup. That is real moss on my face. That is oatmeal and dirt in my hair, and steel wool. They were gonna make a mask, but [Lynch] says, ‘No! I don’t want any of that. I want to see every bone structure, I want to see the green eyes.’ So he had them put it on with a tweezer. It took over 12 hours.”