Michael Roemer remembers the first time he saw himself in a mirror. He was already 12 years old. The mirror stood above a sink in the bathroom of the dormitory he lived in as a student at the Bunce Court boarding school in southeast England, where he had been sent as a young Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany. “Surely we must have had mirrors back home in Berlin, and in store windows and all that, but I’d never seen myself,” he says. “And suddenly, here I was, in the bathroom. I looked up, saw myself, and I said, ‘That’s me.’” He adds, with a chuckle, “Until that moment, I didn’t think I was real.”

Roemer has been around a long time — he just turned 97 — but it’s been a running theme throughout his life and career that it can take some time for him to get noticed. This week, two extraordinarily devastating films he made more than four decades ago will finally receive proper theatrical releases via the independent distributor The Film Desk, as the 1976 documentary Dying and the 1982 scripted feature Pilgrim, Farewell open at Film Forum, ahead of a national expansion. Both briefly aired on PBS in their day but are now almost never screened and have long been unavailable on video.

This is not the first time — or for that matter the second, or third — that this has happened to Roemer. In 2022, The Film Desk also restored and released his long-forgotten 1984 feature Vengeance Is Mine. With its patient and observational style, its intimate conversations and austere performances, Vengeance is Mine was a revelation — like the unearthing of a lost classic pointing towards a path American independent cinema had not taken. The film’s reclamation came 33 years after another remarkable discovery: Roemer’s crime comedy The Plot Against Harry, shot in 1969 but unseen for decades because of failed preview screenings, had finally done the festival rounds and gotten a release in 1989. (Roemer had decided to give that picture another chance after he overheard a video technician laughing while transferring the film to video; the director had intended to give VHS copies of his work to his kids as gifts.) His 1964 film Nothing But a Man, about the struggles of a newlywed Black couple in Birmingham, Alabama, did actually get released in its day, and even won several awards at the Venice Film Festival. (Malcolm X was reportedly a fan.) But the subject matter limited its commercial prospects at the time, and it was long unavailable until a 1993 re-release and a subsequent restoration in 2012.

Roemer, who made a living teaching film at Yale for nearly 50 years, has always been exceedingly modest about his work, and doesn’t know how people will accept the two “new” films. Dying follows three terminally ill individuals and their families in the last months of their lives, presenting these people with a minimum of fuss and sentiment. You might find yourself crying, but you won’t find many tears onscreen. Still, Roemer’s camera remains close, unswerving, privy to startlingly candid moments. The wife of one patient confesses that it would be easier if her husband died quickly so she can remarry while still relatively young; she fears the idea of raising two teenage boys as a single mother.

Though the protagonist of Pilgrim, Farewell doesn’t particularly resemble the people depicted in Dying, she is also terminally ill, and she shares with some of them an anguished uncertainty about how to react to her imminent death. Kate (Elizabeth Huddle) is alternately bitter, cutting, cavalier, distraught. Like several Roemer protagonists, her mood can switch at a moment’s notice — a phenomenon we almost never witness in typical movies, but one that feels uncomfortably true to life. There are no bromides here about the nobility of suffering or beating the odds; we sense that Kate has passed those stages before the movie even begins. Now faced with the end, neither she nor the people around her (which includes her carpenter boyfriend, played by a young, strapping Christopher Lloyd, who began shooting the legendary TV series Taxi around this time) know how to react.

Bleak though his films may be, talking to Roemer is a consistently enchanting and enlightening experience. His spirited fondness for strange stories and his raconteur’s ability to conjure a scene are unmatched. And at the time of our conversation, he informs me he’s still hard at work.

How much do you remember of Germany before you left?

I was 11 when I left. I had a pretty clear picture of where I was and who was around me and so on. My clearest memory, of course, is being frightened and being helpless. My parents were very sad people, so some of that left a mark on me certainly.

What are your memories of the Kindertransport?

There was a train of about 30 children, and we gathered at a railroad station. I think I was the only child who didn’t cry. I was probably quite numb. My mother said that many of the parents who saw us onto the train took taxis to another railroad station in Berlin through which the train was going to pass, and they waved to the train as it went through the station without stopping. I do remember crossing the border into Holland. The Dutch people must have seen other trains like it come through, and they were at the station platform with lemonade and cookies. I remember being very relieved to be out of Germany, even though I didn’t understand what was going on.

In Holland, we all got on a boat, at a port outside of Rotterdam, I believe. We crossed to Harwich, on the east coast of England. It was an overnight trip. We were given a box with food, and we took a train and ended up in a theater in London. All the children were sitting on the stage. I remember looking out into the dark auditorium. The curtain was open, and our names were called out, and somebody in the audience would stand up and claim the child whose name had been called. My sister was three years younger, and she and I were just about the last people on that stage. We were picked up by a woman who had been our pediatrician and taken that evening to the school where we spent the next six years. It was a big manor house in Kent, in southern England.

Here’s a very odd story, but refugees have very odd encounters; the paths of people cross in the strangest way. When I was younger, we had spent a summer holiday in a hotel near Hamburg, and I had a room of my own, which was detached from another suite. Our governess and my sister occupied another room somewhere, but my room didn’t belong to that suite; it belonged to this other suite, and it had a door that went into the bathroom of that other suite. On my bed, I could sit up and look through the keyhole into that bathroom. I never saw anything very revealing, but of course I was curious. One day, as I looked through the keyhole, I looked into another eye! It was a little girl with whom I used to play all day. She was in that other suite, and she was looking through the keyhole as I was. So now, three years later, when I walked into that big manor house in the middle of the night in England years later, who is the first person I saw coming down the stairs? This girl! And she and I never exchanged one word. This was a boarding school of 120 children. We all knew each other. Over the years, we would talk to everybody at one point or another. But she and I just stayed away from each other. It’s like we knew this secret about the other person.

You’ve said that it was at this school in Kent that you first became interested in art and drama.

There was a wonderful man there named Marckland who always said that I adopted him. His widow, who got to be very elderly, later said to me, “Michael, you were his son.” So, I was very lucky. I never really knew my father, and I barely knew my mother. This man had been a theater director in Germany and in Spain as well, and he came to work in the garden and stoke the boiler. I remember I just decided he was my father. It was he who showed me how to work. I was a terrible actor. He put on some plays, and one was Saint Joan, the Shaw play, and he asked me to play the Dauphin. Everybody else seemed very good in the rehearsals, but I didn’t know what to do. We did these scenes over and over and over. I was totally lost.

One day, I showed him a laudatory comment from a teacher on a paper I had written for a class. I was proud. I was probably 14. And he said, “Well, that’s what it should say when you perform in Saint Joan.” I said, “I don’t know how.” And he looked at me, and he said, “That’s how.” It’s like he saw the whine, the sense of helplessness and self-pity in me, and he pointed to it. And from then on, I could play the part. That gift, I think he woke up in me somehow. If somebody is lying on the floor and doesn’t know how to play the scene, I can start to identify with that person simply by lying on the floor. It is hard to describe. I often felt like this person who had never seen himself and who had no identity. In a funny way, that allows you to become anybody. You’re not very clearly defined. I think it goes back to the whole experience of not existing. It triggers something in you. You’re either going to go under or you’re going to survive. You have to keep proving that you exist. I think that’s why I tried to paint. That’s why I wanted to make movies.

Pilgrim, Farewell (1982).

Photo: Film Forum

Do you remember the specific point at which you realized you wanted to make movies?

I remember seeing a French film that I don’t particularly like anymore. It was shown by a political organization at Harvard that raised money for various causes. I walked back from the lecture hall where the film had been showing, and I said, “That’s what I want to do.” But I had no idea how I would go about it. One day, there was an ad in the Crimson that said, “Anyone interested in film?” There was no activity on film at all other than these screenings. So I went to Leavitt House, and there must have been about 50 undergraduates there. At the second meeting, there was a decision, made democratically, that everybody who wanted to make a film should write a script in the summer, and then a committee would select one. Next fall, there was a meeting, and they asked for the scripts, and I was the only person with a script! Nobody understood my script, but the script committee, which I was not on, had no choice but to pick my script. Then came the decision of who was going to direct the movie. “Who’s directed a film yet?” Nobody had. For once, I spoke up for myself and said, “Well, it’s my script, so I think I should direct.” And they all agreed! So that’s how I got through. It’s insane. It’s the old Woody Allen joke about how most of life is just showing up. My life has been just like that. We went into the city, and we just stopped traffic. Nobody stopped us from stopping the traffic. We all looked like children, of course.

That film, called A Touch of the Times, might be the first feature film produced at an American college. How did you get into Harvard in the first place?

Oh, another weird story. My aunt had come to the United States in 1932, and she was a doctor. She in effect saved all our lives. After the six years at school in Kent, they finally allowed non-combatants or people of no consequence to travel across the Atlantic. So, early in 1945, my sister and I went to the United States. When I came to Boston, my aunt said, “What are you going to do?” I said, “I would like to work in theater.” She said, “That’s not very realistic. You better go to college.” I said, “Where should I go?” She said, “There’s a good school across the river, if you can get in.” I had never heard of that school. She sent me to meet with someone whom she knew, a kindly man with an insurance company in Boston who was sort of like a character out of Dickens. He sat facing the corner at his desk. He said, “Well, why don’t we meet in the Harvard Yard?” I’d never even been to Cambridge. I got there taking a couple of street cars. He took me into a building. There was a man behind a desk. I had this Cambridge school certificate with very high grades; it’s what you do when you graduate at the age of 16. The man behind the desk looked at the certificate, and he held it up and said, “We’ll take that.” And I was in. Much later, I found out that that was the Dean of Admissions. I mean, this is a terrible story in many ways.

Oh, my God.

And the man who had introduced me was the secretary of the Boston Harvard Club! I had no idea where I was. I understood nothing. The United States was totally incognito to me. It took me years to understand how things worked. I had no money at all, so I had three jobs during college. The first day, I was in my dorm room, which was right on the ground floor. My aunt said to me, “It’ll take you 20 years to live like this again.” She was absolutely right. Three meals a day, seven days a week, and you could order seconds. I came from rationing. We never saw an egg in England. At Harvard, I couldn’t afford the undergraduate uniform, the three jackets and all that. People brought me clothes that they didn’t want.

Over the course of your career, you only made a few feature films, most of which seemed to have been forgotten. Fast forward to now, it must be very gratifying to suddenly have these films back out in the world.

It’s very odd. It feels like a posthumous thing, like dying and seeing what’s happening to your work. The thing that makes me happiest is the response to Vengeance is Mine. The young people really like it. When I showed it to my colleagues at Yale, they didn’t understand it. They weren’t being mean or anything. And then of course The Plot Against Harry was a complete disaster. I was convinced that I had made this terrible mistake. The crew and the cast came to the first big screening — a screening for them — and nobody liked the movie. I had neighbors whom I invited to another screening, and they came out and said, “Mike, we don’t know what’s going on in your movie.” And 20 years later, when the film was finally released after the New York Film Festival, I invited them to see it again, and they didn’t remember they had seen it. I asked them afterwards, “Did you understand it?” And they said, “Yeah, sure. Why?”

Actually, I’m afraid Pilgrim, Farewell is the one that people have the most trouble with. It’s more arm’s length. We don’t want to know the dark side of ourselves, and there’s some dark stuff in that film. But that’s one thing about theater or film that’s useful. People who have darkened stuff in themselves or feel like they’re outsiders — they think, This film makes me feel like I’m not alone. At least, that’s how I feel. But people have really hated that film. I’m not looking forward to that screening.

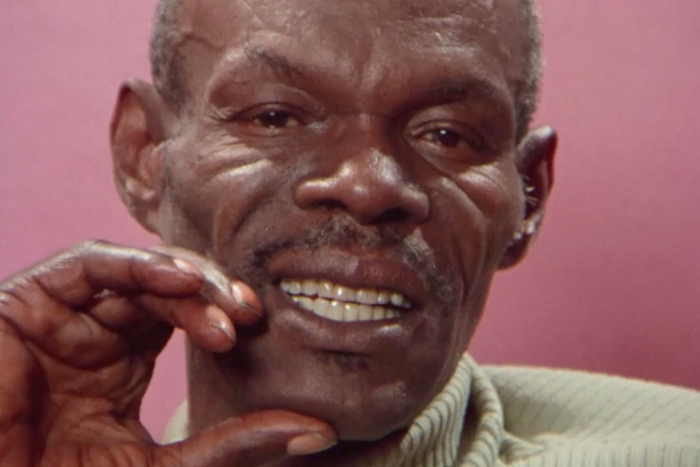

A still from Roemer’s 1976 documentary Dying.

Photo: Film Forum

How did Dying come about?

I’d made a lot of educational films, close to a hundred, and some of them were shown at WGBH in Boston. They had started this project about dying, and the National Endowment for the Humanities was willing to fund the production. But their original idea was to make four half-hour films: about dying and painting, dying and poetry, dying and music, and then a half-hour film about funeral customs all over the world. They asked me to make them, and I said, “I’m sorry, but I don’t think I can do that. I won’t.” They said, “Well, what would you do?” And I said, “Well, the only thing I think I can do is find people who are willing to let us film with them when they’re dying.” Because a lot of people have been married and divorced and they can talk about things like that, but nobody has died to come back that we know of.

I can’t imagine it was easy to find people willing to be filmed.

I met a lot of people who were on the edge of dying, and it got very difficult. It got harder and harder. You didn’t become immune to it at all. I remember going into one room and finding it hard to even open the door — this feeling of turning the door handle in one more room, to see somebody on the verge of death. And when I said that to one of the nurses, they said, “Oh, of course, it’s understandable. Because when we go into a room, we can do something, and you can’t do anything. We can pour water or adjust the sheets or help the man up or whatever.” It was the hardest project I ever did.

Was there something about the story of Dying that you felt you hadn’t explored or something you wanted to say further, which led you to make Pilgrim, Farewell?

No. I had written Vengeance Is Mine, which I would make a few years later, but I took it to a Ford Foundation-funded project at PBS, and the woman who read the script was so condescending about it. She said, “You don’t know how to write.” I went home, and I was so angry that I sat down that afternoon and said, “I’m going to write something that has such a small cast and is so confined that I can find the money myself, and I don’t have to depend on public funding or whatever.” That’s how Pilgrim, Farewell came about. It took me a year and a half to write that script. I wrote it for four people. It’s a chamber piece. I wrote a lot of it up here in Vermont. I wanted to have such a small production that they couldn’t stop us.

Pilgrim, Farewell is a small cast, but it’s also a great cast. And there’s Christopher Lloyd, who was on Taxi right around then, which turned him into a star.

He asked us whether he could go out to L.A. to do a show with them to see how it would work. And we said, “Fine.” He came back, and he was on Taxi immediately afterwards. In many ways, it was the happiest, most unusual film crew and production. We were up in the woods in Vermont, in a little town called Post Mills, which had four houses. People would come and visit the crew, and they’d always say, “Can we work with you? Can we stay here?” But there really was nothing for them to do. There was just something about that small unit working very intensely in the woods.

What are you working on now?

I have this long project, and thank God, it’s coming to an end soon. It’s a book, called One of You, and it’s about a storyteller, namely myself, and how I evolved from being a child in Berlin who was pretty close to getting killed, and then went to England and then the United States, and instead of going to the Lower East Side where my fellow immigrants made their landfall, through circumstances completely out of my control I went to Harvard, and my life has been like that ever since. It all just happened. It wasn’t that long ago that I came up with that title, One of You. But it’s how I feel. I’ve become an American and I’m one of many now. I’m no longer part of an elite or part of a special community. I’m just like everybody else. That’s very important to me.